Edvard Munch Biography

Edvard Munch was born in Norway in 1863 and, with the notable exception of the two decades from 1889 to 1909 spent traveling, studying, working and exhibiting in France and Germany, he lived there until his death in 1944. He was active as a painter from the 1880s until shortly before his death, though the greater part of his oeuvre, and certainly the better-known part, was produced before the early 1920s. During his lifetime of work, he made one of the most significant and enduring contributions to the development of Modernism in the twentieth century. In his themes and subject matter, in the manner in which he gave voice to these, and in his handling of paint and the graphic media (especially woodcut and lithography), Munch was profoundly original and radical. He is one of the handfuls of artists who have shaped our understanding of the human experience and transformed the ways in which it might be visually expressed.

Munch's nomadic and self-imposed exile's life in Europe, from his mid-twenties to mid-forties - especially in the cosmopolitan, creatively fertile centers of Paris and Berlin - was undoubtedly vital to the shape of his art. It established the necessary detachment from the 'untroubled communal myths' of his homeland and the troubled passage of his young manhood. On the one hand, he was freed from the constraints of his past, and the real and perceived limitations of provincial life. On the other hand he was closely associated with the largely Nordic avant-garde writers and artists of his day who shared and promoted his belief in the necessity of using private, subjective experience to create 'universal' statements and imagery. this was the ambiance in which Munch's originality and personal convictions flourished. His was the beginning of an age that celebrated the life of the individual rather than of community or society.

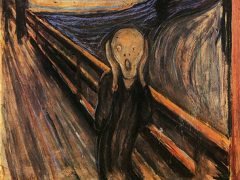

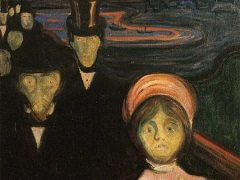

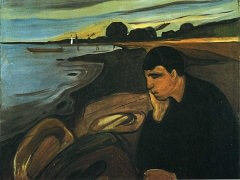

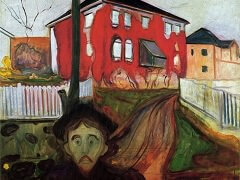

Perhaps more than any other artist, Munch has given pictorial shape to the inner life and psyche of modern man, and is thus a precursor in the development of modern psychology. His images of existential dread, anxiety, loneliness and the complex emotions of human sexuality have become icons of our era. Many of us know such images as The Scream, Anxiety, Melancholy, Jealousy, The Kiss, Madonna, Vampire, and The Dance of Life. In an unfolding and often only loosely connected series of paintings, drawings, and prints, Munch developed these great themes of Angst, Love, and Death during the 1890s - a project he calls The frieze of life - and repeatedly returned to them until the end of his life.

Munch's 'quest for a distilled, elementary from and image that could speak for all of the human experience is best understood within the framework of late nineteenth-century art. For, while we rightly celebrate Munch as a Modernist, radical and singular in his contribution to the modern world, it is important to recognize how deeply embedded and formed he was by the echoes and modes of the fin de siecle - nowhere more so than in his representation of women and sexuality.

Formed by the traumatic events of his childhood - the death of his mother from tuberculosis when he was aged five, his own debilitating illnesses and his beloved older sister's death (also from tuberculosis) when he was thirteen and she barely fifteen - Munch early on rebelled against the dogmatic, fervent religious beliefs of his father and the repressive mores of the bourgeois society which dominated the Kristiania (Oslo) of his youth. As a young art student he associated with the rebellious, 'Bohemian' artists and writers of Kristiania and was quick to respond to the intellectual and aesthetic revolutions brewing around him. Many artists had been persuaded to return to Norway from France by a growing nationalistic spirit and wish to rebuild the Norse identity, fuelled in part by the continuing political Swedish domination of their ancient land. They brought with them an impetus to change. The literary kristiania-Boheme, led by radical thinkers such as Hans Jaeger, along with the artistic community, joined forces with the radical politicians of the time who were working to achieve women's liberation, an eight-hour working day and universal suffrage. One of strongest influences on Munch's development was the somewhat older artist and critic, Christian Krogh whose adoption of the Realism of old masters such as Leonardo da Vinci, Titian, Diego Velazquez, Caravaggio, Vermeer, and Rembrandt, formed a distinctive alternative to the romantic naturalism which had dominated Norwegian art for much of the century. It was in this milieu that Edvard Munch came of age.

Berlin was crucial to Munch's evolution. It was here in the early 1890s that his art found its first widespread reception and recognition; and here too, after 1900, that the level of public acknowledgment, the numerous commissions fro both portraiture and mural decoration, and the emergence of patrons, such as Dr. Max Linde, and his wife Marie Linde, enabled him to earn his living as an artist. In Berlin in the early 1890s, amongst his peers - the cosmopolitan and largely Nordic circle of writers, critics and philosophers - Munch found also the intellectual stimulus and philosophical attitudes that validated the underpinnings of his art, whose beginnings were formulated in the fervent intellectual and sexual radicalism of the Kristiania-Boheme.

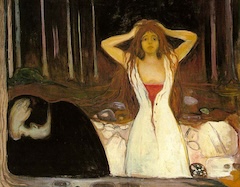

Combined with the recently encountered intensity and anguish of erotic love, this rich brew of emotional, intellectual and physical experience formed the substance which nurtured Munch's art and which would endure for this emotional intensity in his discussion of the celebrated series of images known as The scream and Melancholy; and there are further reflections on the sequences of paintings and prints embodying the power of erotic encounters and subsequent states of jealousy in Elizabeth Cross's essay 'Woman, Love, Jealousy). Munch scarcely deviates from the coherence of his imagery - and the later landscapes, figure studies and even some of the portraits seem to bear a direct connection to the concerns and expression of The frieze of life. Munch's art is essentially inclusive.

Throughout his life Munch made portraits, both informally of family members and of his lovers and friends, and also fulfilling private commissions, on a personal level, his work in this genre encompassed the early portraits of his beloved sister Inger especially, and portraits of the Kristiania Bohemians, Hans Jaeger and Christian Krohg. In Berlin he again painted those in his circle, such Marcel Archinard, and his Polish literary friend Stanislaw Przybyszewsky. But there were also official portraits: the German banker and art patron Walther Rathenau, and Dr. Linde, the medical specialist who befriended him and who commissioned a version of The frieze of life for his children's study.

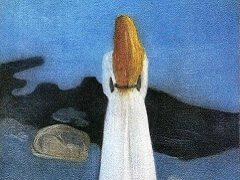

Munch's depictions of women are well known and celebrated - perhaps because of their singular directness about sexuality and their emotional impact. Art history has been inclined to judge Munch's imaging of women as bordering on misogynistic and compliant with the extreme stereotyping of the female which characterizes Symbolist art. While there are certainly many examples which are consistent with this assessment, especially in the early depictions of female sexuality and erotic power in The frieze of life, there are as many which demonstrate a nuanced, sympathetic and perceptive understanding of women, both collectively and as individuals. The tenderness expressed in the numerous depictions of his sister Inger, the admiring recognition of strength, wit and character in portraits of friends such as Aase Norregaard are matched by an unambiguous recognition - in the drawings of Consolation and Weeping young woman and the depiction of emotional states such as loneliness in Two human beings.

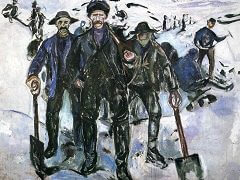

In 1908, following a period of deep crisis and heavy drinking, Munch reached an emotional breaking point which necessitated a period of hospitalization. After his recovery there was a significant change in the appearance of his art, despite the frequent revisiting of The frieze of life themes. With few exceptions, lyrical quality and calmer mood are evident in his painting and increasingly he turned to themes and subjects drawn from the external world: landscapes and figure studies - nudes, bathers - including heroic images of rural and urban labor. While he continued to make prints, these were largely re-workings of earlier subjects, though they remained experimental and innovative. He experimented with photography too, recognizing its potential both as a medium in its own right and as an aid in pictorial inventions, in composition, and in establishing an immediacy of experience, a sense of modernity. He explored photographic self-portraiture, but also used photographs as a simple record of a figure or figures to be used in later compositions.

After the crisis and his recovery, his painterly style becomes very free, fluid and expressive - and often summary in ways that are surprisingly contemporary. There is a rich variety of imagery and mood in the work of the last three decades of his life. Yet it too exhibits qualities which are intensely personal and felt, and which mirror the artist's internal state as much as they do the external world. The companion of his Berlin days and owner of the emblematic face personifying jealousy in that cycle of paintings and prints, the Polish writer Stanislaw Przybyszewski, wrote that Munch's landscapes were 'found in the soul'. Even as they grew more naturalistic and less shaped by the fluid, linear harmonies and stylist manners of the Symbolists and Synthetists, Munch's landscapes remained fused with personal resonance and meaning.

The experience of the landscape was not as central to Munch's art as it was to the work of his contemporaries and in Scandinavian art history in general. Perhaps that has much to do with his long absences from Norway, living in the cosmopolitan and urban centers of Paris and Berlin during his formative years. For the generation of Norwegian artists before Munch, for his contemporaries and for those following him, the idea of landscape as a repository for nationalism, for identity, for the complexities of human experience, and for the mystical or sublime, was crucial. For Munch, however, although he produced a substantial number of landscapes during his lifetime, this was not the vehicle through which his understanding of human experience was primarily expressed. He largely eschewed the sacred tales and hallowed figures of legend and history, and the reading of landscapes as sites of nationalistic belonging and possession, either literal or symbolic in subject matter or motif. Despite this, he was far from indifferent to the particular attributes of his native terrain. In all the years of his self-imposed exile, he scarcely missed a single summer in Norway, usually spending the warmer months in the little coastal two of Asgardstrand where he acquired his first property, and whose rhythmic coastline forms the mise en scene for many of the dramas and soliloquies of his early paintings. Indeed, the few landscapes he felt moved to paint outside Norway, in Germany, reflect the topography and seasonal extremes to which he was habituated. And following his permanent return to Norway in 1909, the moods and seasons of his surroundings increasingly engaged his attention. These too may be understood within the embrace of The frieze of life - for in nature's ruthless indifference and winter severity, in the frozen earth's dramatic eruption each spring and ascent from darkness into summer's plenitude, the cycle of life and death is constantly present. the seasons are indelibly impressed on the human psyche and equate with inner experience. In the extremes of Nordic lands, nature and human experience are inseparable.

No longer shall I paint interiors with men reading and women knitting. I will paint living people who breathe and feel and suffer and love."

- Edvard Munch

For Edvard Munch this return to the landscape of his homeland, in his middle and old age, provided the metaphoric language with which to express his theme of loneliness and isolation, of love and longing, and of reconciliation with death. The landscape finally freed him.