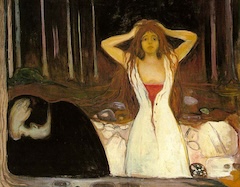

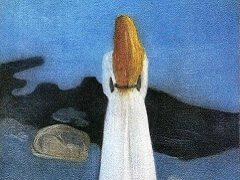

Madonna, 1894 by Edvard Munch

Originally called Loving Woman, this picture can be taken to symbolize what Munch considered the essential acts of the female life cycle: sexual intercourse, causing fertilization, procreation and death. Evidence for the first is in the picture itself, an intensified, spiritualized variation in the nude of the 'mating' pose, the woman depicted as though recumbent beneath her lover. The ethereal beauty of her face was said to resemble both Dagny Przybyszewska and her sister Ragnhild Backstrom. Procreation was implied by the decoration of the original frame, later discarded, on which were painted drops of semen and an embryo. That Munch associated the image with death is clear from his own comments on the picture, in which he sees it as representing the eternal cyclical process of generation and decay in nature. He continually connected love with death: for the man, because it eviscerated him, for the woman, because, following Schopenhauer, he appears to have thought her function ended with child-bearing.

To call the picture Madonna is not in-appropriate if the word is understood metaphorically, for Munch, unable to accept Christianity or a personal god, regarded the continuous generation and metamorphosis of life in a religious light, subsuming its spiritual as well as its material components. The blood-red halo around the woman's head could be considered the spiritual counterpart to the touches of red on her lips, nipples and navel. She seems to float within curing bands of colored light suggestive of art nouveau. Far from deforming her, however, they look like a supernatural emanation, possibly deriving from the spiritualist notion of an aura, surrounding all individuals but only visible to mediums.

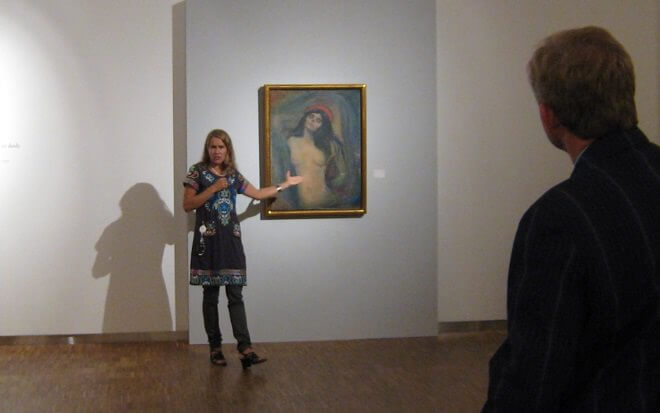

Like many other modern artists, during his entire career, Munch likes to insistently works and reworks each idea. For example, The Scream exists in three different version, and Munch left at least five versions of Madonna. Even with different themes and variations, Munch's works always represent a fixation on subject matter, and over time they become elements in a series with a life of its own. From Claude Monet in his pursuit of natural light until his technique all but effaced the subject of his Water Lilies, from Piet Mondrian's grid series to Jackson Pollock's bare numeric titles that somehow include both One and Number One, Modernism found in series at once a point of origin and a free play that cannot cease.